1. Introduction: Why Construction Cost Budgeting Matters in 2026

Construction cost budgeting is the backbone of profitable and predictable projects in 2026. Accurate cost budgeting aligns design intent, market prices, contractor capability, and client expectations into a single financial roadmap that guides all decisions from concept to handover. When the budget is realistic and well-structured, teams can plan procurement, manpower, and cash flow with confidence.

Industry data shows that 70% of a typical construction budget goes to hard costs such as labor, materials, and equipment, while roughly 30% covers soft costs like design, permits, insurance, and fees. At the same time, global studies indicate that a very high share of projects still exceed their original budgets, often by double‑digit percentages, due to inaccurate estimates, scope changes, and poor cost control.

In 2024–2026, construction cost inflation has moderated compared with the extreme spikes during 2021–2022, but many markets still experience year‑over‑year cost escalation in the low single digits, and select sectors see higher increases. Travel, logistics, and site‑related expenses for field teams are also expected to increase by around 5–7% globally in 2026, putting additional pressure on budgets if not forecast correctly. For contractors, developers, and project owners, mastering construction cost budgeting in 2026 is no longer optional; it is a competitive necessity.

Table of Contents

2. The High Cost of Getting Budgeting Wrong

Cost overruns are not rare exceptions; they are the norm in many markets. Global analyses over multi‑decade periods indicate that a large majority of construction projects suffer cost overrun, with average overruns often in the range of several tens of percent above the baseline budget. Some studies have reported extreme cases where overruns can approach or exceed 80% above initial estimates on complex capital projects.

The consequences of poor cost budgeting go far beyond reduced profit. When costs blow out, projects face disputes, claims, and significant schedule delays. One global claims analysis found that cumulative delays across major projects studied amounted to hundreds of years and that disputed costs averaged around one‑third of project capital expenditure. Such disputes damage relationships, erode margins, and can impact the reputations of contractors and owners in the market.

Overrun patterns also influence portfolio‑level decisions. Large overruns on one job can absorb cash that was meant for future bids, equipment investments, or strategic expansion. Studies of builders in North America and Europe show that persistent budget overruns on residential and commercial projects reduce the number of new jobs firms can safely take on, constraining growth. In emerging markets, overruns linked to design errors, late scope changes, and funding gaps are a major cause of stalled or abandoned projects, particularly in infrastructure and public works.

3. Core Concepts in Construction Cost Budgeting

3.1 Hard Costs, Soft Costs, and Contingency

Most construction budgets can be organized around three primary blocks: hard costs, soft costs, and contingency. Hard costs cover direct construction expenses such as structural works, finishes, MEP systems, labor, and equipment. Soft costs include design fees, permitting, approvals, utility connections, legal fees, insurances, and project management overheads.

A commonly referenced rule of thumb is that hard costs account for around 70% of the budget, while soft costs and other indirect charges make up the remaining 30%. On top of this, professional guidance often recommends adding a contingency allowance between 3–10% of the total project cost, depending on project complexity, design maturity, and risk profile. Contingency is not a catch‑all for poor planning; it is a controlled reserve for genuine uncertainties such as minor design refinements, unforeseen ground conditions, or modest market price movements.

3.2 Direct vs Indirect Costs

Direct costs are those that can be traced to a specific project activity or BOQ item: for example, cubic meters of concrete, square meters of tiling, or hours of crane operation. Indirect costs are overheads that support multiple activities or the entire project, such as site management staff, temporary facilities, utilities, site security, and head‑office allocations. Misclassifying indirect costs or under‑allowing for them is a common reason why “on‑paper” unit rates do not translate into actual profitability on site.

For robust budgeting, each cost item should be tagged not only to a work package or cost code but also to whether it is direct or indirect. This enables better forecasting of cash‑flow curves and clearer understanding of where savings or overruns are originating. It also helps in benchmarking across projects, since overhead percentages, preliminaries, and site establishment costs vary by project type and location.

3.3 Cost Baseline, Allowances, and Contingencies

The cost baseline is the approved budget for the project’s scope, distributed over the schedule, and used as the reference point for performance measurement. Within that baseline, allowances are provisional sums set aside for specific elements that are not fully defined, such as landscaping, specialized finishes, or technology systems. Contingency is a general reserve for unidentified risks, whereas allowances are tied to identifiable but yet‑to‑be‑detailed work.

Once the baseline is approved, all subsequent variations, change orders, and risk utilizations should be logged against it. Mature organizations often separate design contingency (for scope definition changes), construction contingency (for execution‑stage uncertainties), and management reserve (held at a portfolio level). Clearly separating these buckets improves transparency when negotiating with clients and when reporting internally on performance against budget.

4. Building a Robust Construction Budget: Step‑by‑Step

4.1 10‑Step Budget Development Checklist

Use the following checklist when setting up a project budget from concept to detailed baseline:

- Define scope and objectives clearly

- Select an appropriate estimating method for the project stage

- Develop a work breakdown structure (WBS)

- Prepare quantity take‑off and unit rates

- Include indirect costs, overheads, and preliminaries

- Assess and price risks

- Incorporate escalation and inflation assumptions

- Structure the budget by phases and cost codes

- Review with key stakeholders

- Freeze a cost baseline and change control process

4.2 Structuring the Budget: Example Table

A simplified structure for a mid‑size building project budget might look like this:

The exact percentages vary by project type, procurement model, and market conditions, but this structure ensures that no major cost block is overlooked.

5. Estimating Techniques: From Concept to Detailed Take‑Off

5.1 Key Estimating Methods

Modern construction cost budgeting relies on a toolbox of estimating methods rather than a single approach. Common methods include:

- Analogous estimating: Using historical costs of similar projects and adjusting for size, location, and time.

- Parametric estimating: Using cost per functional unit, such as cost per square meter of GFA or per hospital bed, often supported by statistical relationships.

- Bottom‑up (detailed) estimating: Building the estimate from detailed quantities and unit rates for each activity or component.

- Resource‑based estimating: Pricing labor, equipment, and materials separately for each activity based on productivities and durations.

Early in the project, analogous and parametric approaches provide fast answers where detailed design does not yet exist. As the design is refined and a BIM model or full set of drawings becomes available, the estimate should transition to bottom‑up and resource‑based methods for accuracy.

5.2 Simple Parametric Formula

A basic parametric budget formula for a building project can be expressed as:Total Budget=A×Cunit×(1+E)+S+C

Where:

- A = total built‑up area (e.g., square meters)

- Cunit = base construction cost per unit area

- E = escalation factor over project duration (e.g., 0.05 for 5%)

- S = soft costs (fees, permits, etc.)

- C = contingency allowance

This formula is useful in feasibility studies to rapidly compare options, as long as the assumptions for unit costs and escalation are taken from current, reputable market data. As the design progresses, each component of the formula should be decomposed into detailed BOQ items with project‑specific rates.

5.3 Bottom‑Up Estimating Workflow (Checklist)

Use the following workflow for detailed bottom‑up estimates:

- Obtain latest drawings, specifications, and BIM model (if available).

- Define measurement rules (standards, inclusions, and exclusions) to ensure consistency.

- Perform quantity take‑off for each trade and activity.

- Assign unit rates based on supplier quotes, subcontractor bids, and labor productivity data.

- Add indirect costs, preliminaries, and overheads.

- Apply location factors and taxes, if required.

- Run sensitivity tests on key cost drivers such as steel, concrete, or labor.

- Review with trade specialists and adjust assumptions where needed.

5.4 Integrating Risk into Estimates

Risk‑based estimating involves quantifying both the probability and impact of cost risks, then reflecting them in contingency or risk allowances. Multiple industry guides recommend using risk registers and, for large projects, quantitative techniques such as Monte Carlo simulations to better understand the possible spread of final costs. Even on smaller projects, structured workshops with design, procurement, and construction leaders can identify high‑risk items such as complex foundations, imported materials, or tight access constraints and assign appropriate cost provisions.

6. Advanced Cost Control Strategies and Forecasting

6.1 Earned Value and Cost Performance

Once construction is underway, earned value management (EVM) provides a rigorous method to track performance against budget. EVM compares:

- Planned Value (PV) – budgeted cost of work scheduled.

- Earned Value (EV) – budgeted cost of work actually performed.

- Actual Cost (AC) – actual cost incurred for the work performed.

From these, key indicators such as the Cost Performance Index (CPI) can be calculated as CPI=ACEV. A CPI below 1 indicates cost overrun, while above 1 suggests cost efficiency. Many modern construction management platforms embed EVM dashboards to provide near real‑time insight into whether the project is spending ahead of or behind the value produced.

6.2 Forecasting Final Cost (EAC)

Forecasting the final cost, often expressed as Estimate at Completion (EAC), is critical for proactive corrective action. A simple approach is:EAC=BAC×CPI1

Where BAC is the Budget at Completion (original approved budget). More sophisticated formulas adjust for schedule performance and known future risks, but even this basic version helps managers quickly see whether current spending trends will breach the budget. When EAC consistently exceeds BAC, the team must either identify savings, negotiate scope adjustments, or trigger contingency and management reserves.

6.3 Value Engineering and Life‑Cycle Costing

Value engineering (VE) is a structured process for improving value by balancing performance and cost. It focuses on functions rather than individual components, asking what each element must achieve and whether there is a more economical way to achieve it without sacrificing required quality.

Life‑cycle costing (LCC) extends the analysis beyond initial construction cost to include operations, maintenance, replacement, and disposal costs over the building’s life. In green buildings and infrastructure, LCC often justifies higher upfront investments in energy‑efficient systems or durable materials that reduce long‑term operating expenses. Several national and international standards provide guidance on LCC methodologies for buildings and infrastructure projects.

7. Technology, Tools, and Software for Cost Budgeting

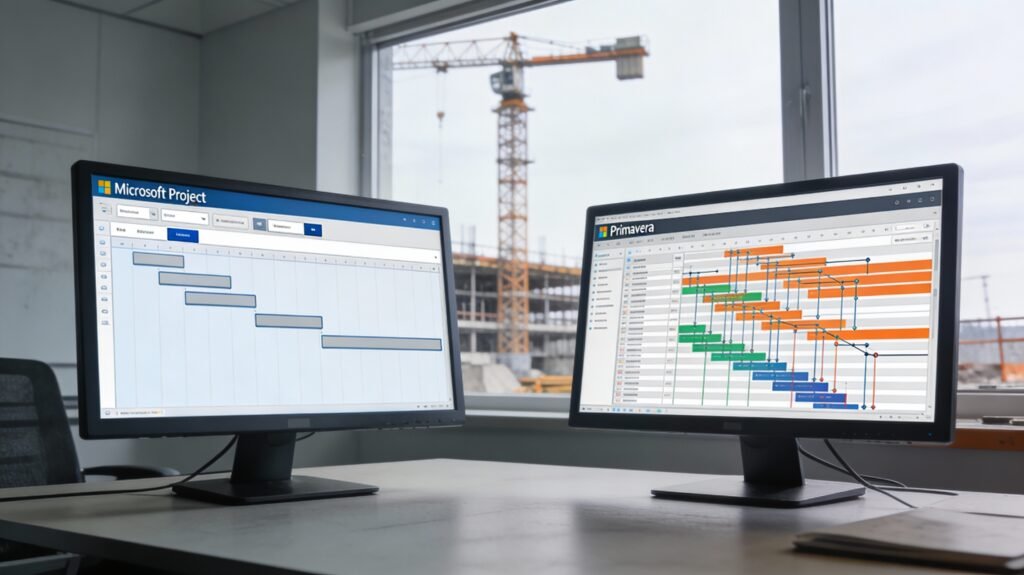

7.1 Estimating and Cost Management Platforms

Specialized construction cost management platforms have become central to effective budgeting, integrating estimating, budgeting, and job cost control into a single environment. Many tools allow contractors to build detailed estimates, convert them directly into budgets, track committed and actual costs, and monitor variances in real time.

Cloud‑based platforms often integrate with accounting systems and project management tools, reducing manual data entry and reconciliation errors. Some providers offer dashboards for tracking key cost KPIs, including committed vs actual costs, cost forecasts, and profitability by project, region, or client.

7.2 BIM and 5D Cost Modeling

Building Information Modeling (BIM) is increasingly used not just for 3D coordination but also for 5D cost modeling, linking quantities and cost data directly to model elements. This enables quantity extraction directly from the model, faster scenario analysis, and better visualization of where money is spent in the building.

AI‑assisted tools are also emerging, capable of scanning drawings or models, classifying elements, and generating early estimates with minimal manual input. When combined with historical cost databases, these tools can quickly suggest cost ranges for alternative design solutions, improving collaboration between designers and cost managers during early stages.

7.3 Field Data Capture and Analytics

Accurate cost control depends on timely and reliable field data. Mobile applications for daily logs, time sheets, equipment hours, and material receipts feed near real‑time information into central systems. Modern analytics tools can then compare actual productivity and resource consumption to planned values, highlighting deviations early.

Some organizations also use drones, scanners, and IoT sensors to track progress and quantities, further improving the accuracy of earned value and cost forecasting. These technologies help reduce disputes over measured quantities and provide objective evidence when negotiating change orders or claims.

8. Common Cost Budgeting Mistakes and How to Fix Them

8.1 Frequent Mistakes

Common recurring mistakes in construction cost budgeting include:

- Under‑scoped estimates

- Ignoring indirect and overhead costs

- Over‑reliance on outdated unit rates

- Weak change control

- Poor integration between budget, schedule, and procurement

- No structured risk assessment

8.2 Practical Solutions

To address these mistakes:

- Standardize WBS and cost codes so every project uses a consistent structure, making it easier to check for missing items and benchmark costs.

- Regularly update cost databases with recent tender results, supplier quotes, and market indices for key materials such as steel, cement, and fuel.

- Implement formal change‑order workflows, ensuring that scope changes cannot be executed without cost and time impact assessment and updated approvals.

- Integrate scheduling and budgeting tools, using 4D/5D models where possible so that schedule changes immediately highlight cost implications.

- Run structured risk workshops at key milestones and quantitatively link major risks to contingency provisions.

9. Worked Examples and Calculations

9.1 Worked Example 1: Quick Feasibility Budget

A developer is planning a 10,000 m² commercial building. Based on recent market data, the average construction cost (hard costs) for similar buildings in the city is about 1,200 currency units per m². Soft costs are typically around 20% of hard costs, and recommended contingency is 7% of total construction cost. Expected escalation over the 2‑year duration is 5% cumulative.

Using the parametric formula:Total Budget=A×Cunit×(1+E)+S+C

Assume:

- A=10,000 m²

- Cunit=1,200

- E=0.05

- Soft costs S=0.20×(A×Cunit)

- Contingency C=0.07×(A×Cunit)

Step‑by‑step:

- Base hard cost = 10,000×1,200=12,000,000.

- Hard cost with escalation = 12,000,000×1.05=12,600,000.

- Soft costs = 0.20×12,000,000=2,400,000.

- Contingency = 0.07×12,000,000=840,000.

Approximate total budget = 12,600,000 + 2,400,000 + 840,000 = 15,840,000 currency units.

This quick calculation gives the developer a realistic order‑of‑magnitude budget before committing to detailed design and procurement.

9.2 Worked Example 2: EAC Forecast Using CPI

Consider a project with a Budget at Completion (BAC) of 50,000,000. Midway through the project, earned value (EV) is 20,000,000, and actual cost (AC) is 22,000,000.

- Compute CPI: CPI=ACEV=22,000,00020,000,000≈0.91.

- Forecast EAC using EAC=BAC×CPI1.

- EAC≈50,000,000×0.911≈54,945,000.

The project is therefore predicted to finish roughly 9–10% over budget if current performance trends continue. This early warning allows management to investigate cost drivers, renegotiate procurement packages, adjust workflows, or consider scope trade‑offs.

10. Real‑World Case Studies

10.1 Case Study 1: Mid‑Rise Residential with Overruns

A mid‑rise residential project in a major city experienced a cost overrun exceeding 15% compared with the approved budget. Sector data for similar projects indicates that more than two‑thirds of builders in the residential and light commercial segments reported budget overruns in 2024. In this case, the main drivers were incomplete early design, late changes to façade materials, and underestimated preliminaries due to a constrained urban site.

Industry research shows that a high proportion of overruns globally can be traced to inaccurate or incomplete design, scope changes, and poor communication between stakeholders. Here, the project team initially used a simple rate per square meter without fully capturing complex façade detailing and access constraints. As design evolved, higher‑spec materials and installation methods were chosen, but the budget baseline was not updated in real time. As a result, by the time tender packages were returned, actual prices exceeded the original allowances by double‑digit percentages.

Remedial steps included re‑running the budget using detailed BOQs and leveraging competitive bidding for subcontractors and suppliers, in line with best‑practice guidance that emphasizes market‑tested pricing and diversified supplier strategies. The team also established a structured change‑order process with the client, aligning each design refinement with formal cost approval. These measures stabilized the final overrun and provided a learning loop for future projects.

10.2 Case Study 2: Infrastructure Project with Major Claims

In a large infrastructure program spanning multiple countries, a global analysis of claims found that disputed costs represented more than one‑third of project capital expenditure, and schedule delays associated with these disputes added an average of many months to project durations. Common issues included design errors, changes in scope, late approvals, and disagreements over contract interpretation.

The project owner responded by strengthening cost governance and documentation. Contract clauses related to variations, escalation, and risk allocation were clarified, and a structured submittal process was introduced to improve communication and reduce design‑related errors. In parallel, independent cost audits and regular risk‑based forecasting reviews were implemented, drawing on practices recommended in industry cost management literature. These interventions reduced the incidence of new claims and shortened resolution times for existing disputes.

10.3 Case Study 3: Cost‑Efficient Commercial Fit‑Out via Value Engineering

A commercial office fit‑out project faced pressure to reduce budget by around 8% without compromising function or safety. Industry guidance on value engineering and sourcing strategies suggests that function analysis, bulk purchasing, and localized procurement can deliver meaningful savings when used carefully.

The team conducted workshops focusing on core functions such as flexibility, acoustics, and energy performance. Alternative materials and systems were evaluated based on life‑cycle cost rather than initial price alone, consistent with recommended value engineering practices. By rationalizing partition types, optimizing lighting layouts, and using locally sourced finishes with similar performance specifications, the project achieved the required savings while preserving key design intent. Long‑term operating costs were also reduced through more efficient lighting and HVAC controls, aligning with broader trends in sustainable and cost‑effective commercial building design.

11. Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1. What is a realistic contingency percentage for construction budgets in 2026?

For most building projects, a contingency between 3–10% of total construction cost is commonly recommended, with lower percentages for straightforward, well‑defined scopes and higher allowances for complex or high‑risk projects. Major infrastructure or projects in volatile markets may require even higher contingencies, informed by structured risk analysis and market studies.

Q2. How should inflation and escalation be handled in construction budgets?

Budgets should incorporate escalation based on credible data for the region and sector, since recent reports indicate year‑over‑year construction cost escalation of a few percentage points in many markets, following earlier periods of higher inflation. Travel, logistics, and certain material categories may escalate faster, with some sources projecting 5–7% increases globally in 2026 for specific cost components. Planners should differentiate between general inflation, specific material trends, and contractual escalation mechanisms.

Q3. What is the difference between contingency and allowance?

An allowance is a provisional sum allocated to a known but not fully detailed scope, such as specialized finishes or equipment, whereas contingency is a reserve for unforeseen risks and uncertainties across the project. Good practice separates these two categories and tracks any draw‑downs separately so that stakeholders understand whether over‑spend is due to scope decisions or genuine risk realization.

Q4. Why do so many construction projects overrun their budgets?

Studies show that common causes include inaccurate initial estimates, incomplete or changing scope, design errors, and poor communication between project participants. Underestimating timelines and ignoring indirect costs also contribute, as delays and extended site presence significantly increase preliminaries and overheads.

Q5. How can digital tools improve construction cost budgeting?

Integrated cost management platforms and BIM‑enabled 5D modeling help teams maintain a single source of truth for quantities, budgets, and actual costs, reducing manual errors and data silos. Mobile field tools, analytics, and automation can provide near real‑time visibility of spending and productivity, enabling earlier intervention when trends diverge from the budget.

Q6. At what project stage should detailed cost budgeting start?

High‑level budgeting begins as soon as a rough concept and size are known, often using analogous or parametric methods. Detailed budgeting using bottom‑up techniques should start once schematic design stabilizes and intensify through design development and construction documentation, with budgets updated at each major deliverable.

Q7. How can owners ensure contractors do not under‑price and later claim variations?

Owners can mitigate this risk by issuing complete and coordinated tender documents, using prequalification to select competent bidders, and evaluating bids for realism rather than simply lowest price. Clear variation and escalation clauses, along with independent cost reviews, support fair risk allocation and reduce opportunities for strategic under‑pricing.

Q8. What is the role of life‑cycle costing in budget decisions?

Life‑cycle costing helps decision‑makers compare alternatives on the basis of total cost of ownership, not only upfront expenditure, which is critical for long‑life assets such as public buildings and infrastructure. Market guidance indicates growing use of LCC in evaluating energy systems, façade designs, and material selections, particularly in green building and ESG‑driven investments.

12. Free Resources for Better Cost Budgeting

Professionals can access several free or low‑cost resources to enhance construction cost budgeting capabilities. Many international consultancies and cost databases publish periodic construction cost trend reports for key markets, providing up‑to‑date indices and insights on material and labor price movements. Industry platforms and software providers also offer webinars, white papers, and quick‑start guides covering estimating methods, contingency planning, and digital cost control practices.

Public agencies and standard‑setting bodies in several countries publish guidelines and templates for capital project budgeting, especially for infrastructure and public buildings. When combined with internal project data and lessons learned, these resources form a strong basis for continuous improvement in cost budgeting discipline.

13. Related Articles on Famcod

(Insert internal links to at least seven Famcod construction management and engineering articles; placeholders below can be updated with actual URLs.)

- Construction Project Planning & Scheduling: Complete Guide

- Risk Management in Construction Projects: Practical Framework

- Construction Contracts and Claims: Basics for Engineers

- Quality Management on Construction Sites: Tools and Checklists

- BIM in Construction: From 3D Coordination to 5D Cost

- Lean Construction Principles for Site Teams

- Cash Flow Management for Construction Contractors

14. Recommended Resources (Books & Courses – Affiliate Ready)

14.1 Books (Amazon Affiliate Ready)

- “Construction Cost Management: Learning from Case Studies” – Practical exploration of real projects, focusing on how budgets, estimates, and cost controls performed across different sectors. [Amazon Affiliate Link]

- “Cost Management in Construction Projects” – Detailed coverage of budgeting, estimating techniques, and financial control aligned with modern industry practice. [Amazon Affiliate Link]

- “Building Construction Costs with RSMeans Data” – Comprehensive cost data reference for North American projects, useful for unit rate benchmarking and early estimates. [Amazon Affiliate Link]

- “Project Management for Construction: Fundamental Concepts” – Explains how cost, time, and quality interact, with sections on budgeting and financial planning for capital projects. [Amazon Affiliate Link]

- “Life-Cycle Costing for Construction Projects” – Focused look at evaluating long‑term cost implications of design and material choices. [Amazon Affiliate Link]

14.2 Courses (Coursera Affiliate Ready)

- Coursera: “Construction Cost Estimating and Cost Control” – A course that covers estimating fundamentals, cost control techniques, and basic forecasting tailored to construction projects. [Coursera Affiliate Link]

- Coursera: “Construction Project Management” – Broader project management program with dedicated modules on budgeting, contracts, and financial planning for construction. [Coursera Affiliate Link]

- Coursera: “BIM for Construction Costing and Estimating” – Explores how BIM and 5D modeling can support more accurate and efficient cost budgeting workflows. [Coursera Affiliate Link]